Nestled along the Konkan coast, Dahanu in Maharashtra’s Palghar district is a landscape where ecology, culture, and livelihoods are intricately woven together. One of the finest examples of this harmony is the traditional practice of sustainable toddy tapping, preserved for generations by the Warli and Bhandari communities. Far from being an extractive activity, toddy tapping here is guided by respect for the palm, the forest, and the rhythm of nature.

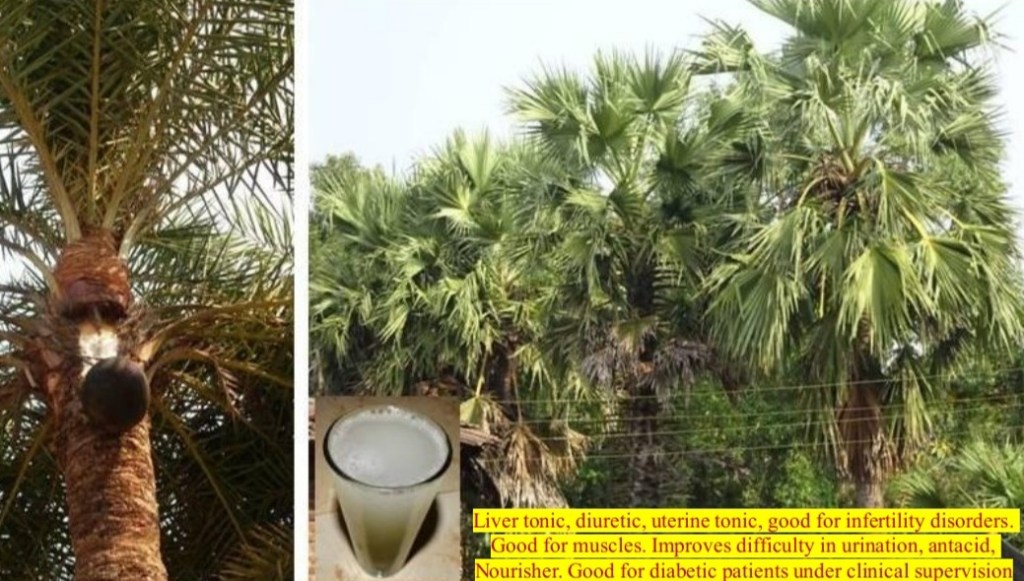

Sustainable tody tapping begins with careful tree selection. Tappers choose only mature Palmyra (tadgola) or date palms and follow a system of rotation across groves. This ensures that individual trees are given adequate time to recover, often resulting in healthier palms and improved fruiting in subsequent seasons.

The toddy tappers make precise, shallow, slanting incisions on the unopened flower bud, or spadix with skilled hands. This allows the sap to flow freely while leaving the structural integrity of the tree intact. Sap is collected in earthen pots, or matkas, whose porous clay keeps the liquid cool and slows down fermentation.

The toddy tappers make precise, shallow, slanting incisions on the unopened flower bud, or spadix with skilled hands. This allows the sap to flow freely while leaving the structural integrity of the tree intact. Sap is collected in earthen pots, or matkas, whose porous clay keeps the liquid cool and slows down fermentation.

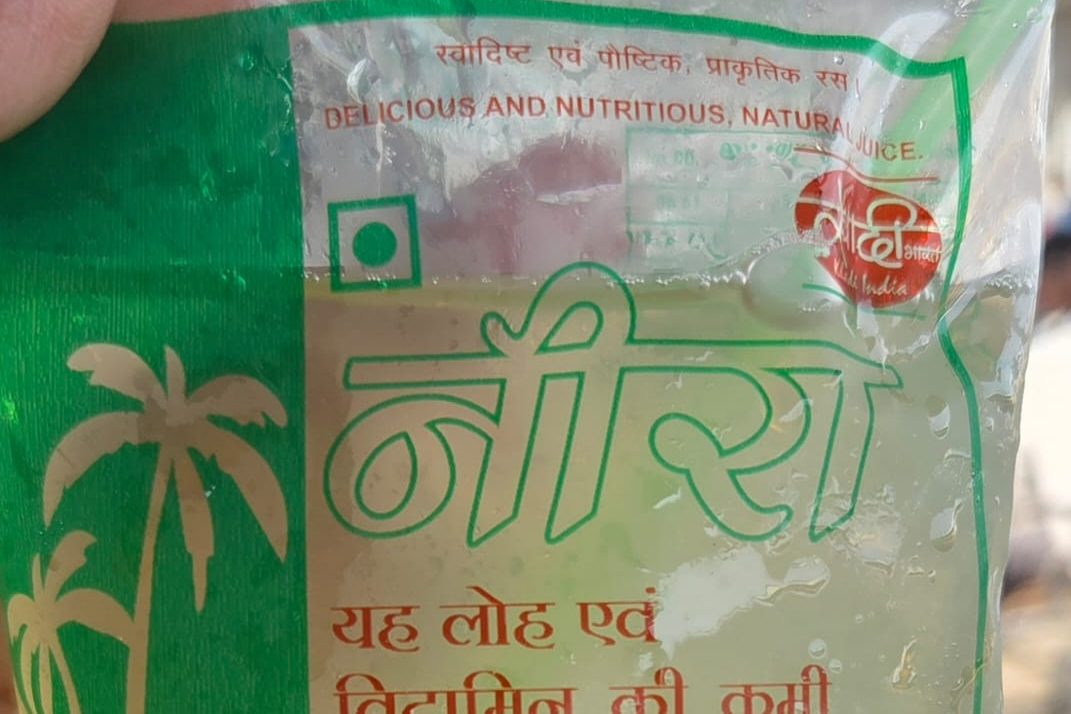

This is especially important when harvesting neera—the fresh, non-alcoholic sap valued for its nutritional benefits.

Toddy tapping carries deep ecological and cultural significance. The palms are truly zero-waste resources: leaves are woven into baskets, artefacts or used for roofing. Regular climbing and cleaning of the crown during tapping is believed to reduce pest infestations naturally, eliminating the need for chemical pesticides.

A Myna relishing Date Pam Sap

This living tradition is also central to Dahanu’s growing heritage tourism. It is supported by the PESA Act of 1996—which permits tribal households to store limited quantities of toddy for domestic or ritual use. Sustainable toddy tapping continues to thrive as a vibrant expression of cultural resilience and ecological wisdom.

Information collected by Dr. Suchandra Dutta from different sources in google and personal observation. Photos clicked at Kainad, Ganjad villeges in Dahanu. Email: greenneev.mumbai@gmail.com